Feature Articles Home

Having completed a work experience placement at Reuters I found a desire to get into journalism, the Broadcast Journalism Degree subsequently followed and an area I particularly enjoyed was the feature writing module. I prefered the slower turnaround required compared to the rush of daily news and found that I could write about topics I was interested in and weren’t overly reported. I also prefered the longer interview formats compared to Vox Pops, which saw me speaking with an MBE, a Fijian family and a Syrian refugee, compared to the average Bristolian wandering around Cabot Circus, no offence.Below are the three feature articles I produced during my final year of study:

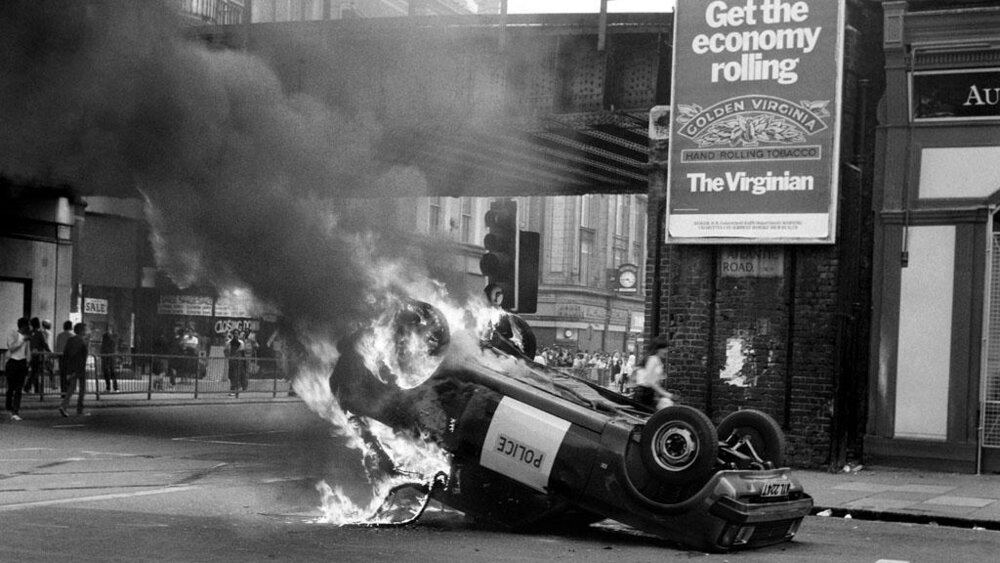

1 - Four decades on from the Brixton riots, frustrations still simmer (News Feature)

Alex Wheatle recalls how the police looked to him and his fellow rioters as the streets of

Brixton calmed down at the end of ‘Bloody Saturday’ in 1981: “We had empowered

ourselves to such an extent that they were the ones now scared of us, rather than us being

scared of them.”

The prize-winning author was one of thousands of Black Britons who took to the streets of

South London’s most renowned district on April 11 40 years ago, when years of building

tensions over police brutality erupted in disturbances that left 279 police officers injured.

“For me there was no doubt in my mind, I had experienced police brutality, I was beaten up

in police cells on two occasions, so there was a lot of anger within me,” Wheatle, who in

2008 was awarded the MBE for services to literature, said.

“So, when I saw the opportunity to get my revenge and take part in an uprising, I took it

with both hands as I felt there was no other justice I could seek.”

Yet despite a public inquiry finding ‘unquestionable evidence’ of disproportionate and

indiscriminate use of stop and search powers against black people as a factor behind the

riots, very little has changed.

Cyndi Anafo, a local DJ and booking agent, was 14 years-old when the riots broke out. She

remembers being unafraid as she watched the scenes unfold on the television in her

family’s living room.

“I had a weird sense of solidarity with the rioters, our parents gave us the knowledge to let

us know that the way we [black people] were always going to be represented in this country

was negative, so I wasn’t afraid, even though the narrative was to be afraid”

While the discrimination and racism that she grew up with remain problems today, Anafo

says the community is facing a new threat: gentrification.

Broadly put, gentrification refers to wealthier people moving into a predominantly working-

class area.

“I think the reason for this continuing trend, is because not enough people in positions of

power are willing to dismantle the existing racist practices and legislations that benefit this

demographic which tend to come into areas and kill the environment, through their bland

whitewashing of these vibrant communities,” Anafo said.

This trend has been ongoing in London’s booming housing market for a while but has

triggered a wider backlash in recent years as it shifts from more suburban South London

areas into inner-city areas such as Brixton and Peckham.

A current example of this is a proposal by US property developers Hondo Enterprises to

build a 21-storey office block in the heart of Brixton. The proposal was initially approved by

the council in the borough of Lambeth but received strong opposition from the community,

causing London Mayor Sadiq Khan to pause the plans and call a public hearing.

Professor Phil Hubbard, professor of urban studies at Kings College London, says some of

the opposition reflects people’s attachment to the past.

“Yes, there is still nostalgia for the high street that used to be but we’re never going to get it

back, we can’t go back to the high street of the 50s and 60s,” Hubbard said.

“However, there needs to be a balance between that touristic gentrified stuff that tourists

would expect anywhere, but also that stuff that’s local and characterful.”

“We shouldn’t get rid of the chicken shops that give kids somewhere to hang around after

school and they can afford, and we shouldn’t get rid of the betting shop that a middle-aged

man can pop into and spend half an hour with his mates. And getting rid of those places to

try and get the others is part of the problem.”

Hondo Enterprises also tried to evict the people at retailer Nour Cash and Carry in Brixton

market, which has sold a diverse range of affordable food for 20 years. However, following

an outcry in the community, an agreement for a relocation of the store was reached.

Hubbard agrees with Anafo on the need for the government to not only amend the issues

raised by gentrification, but tackle Britain’s housing crisis as well.

“If you have rent controls, planning controls and community ownership of land,

gentrification isn’t inevitable,” he said. “But, if you leave things to the market, as the

Conservative government have been doing, in a high-demand environment like London,

then there’s always going to be people looking to maximise their investment and talk up

particular areas.”

Wheatle, who was arrested for his involvement in the riots, still has family living in the area

and is disheartened that the next generation, including his kids, will find it increasingly

difficult to establish themselves in their native Brixton due to lack of affordable housing.

“It’s just so unfair that you cannot remain in the community you were raised in, or your

parents and grandparents settled in. I think it’s such an injustice, I really do.”

When asked whether Brixton is better off now than it was 40 years ago, both Cyndi and Alex

searched for the positives.

“Of course it’s improved, but it’s an improvement for the people that they [the government]

think deserve improvements and sadly, it’s those who have lived here for a very long time

that are the ones not benefitting,” Anafo said.

Wheatle conceded that some of the changes were positive. “For example, on the old

frontline, as we used to refer to Railton Road, you can now visit an art gallery, there’s a

sushi bar, there’s restaurants. In my day there was none of those things. So that’s a good

thing.”

“But the police are still stopping black youths out of proportion to how they stop anybody

else, which needs to be addressed I believe.”

2 - The disappearing island and the family trying to save it (Profile Piece)

Josh Yee Shaw spends most of the year looking after his family’s small Fijian private island,

Nukulevu. This tranquil slice of paradise, no bigger than half a football pitch, has been in

their possession for 5 years under a lease from the Catholic Church.

However, a combination of challenges – from climate change to COVID and over-fishing – is

making Josh, who is 24, his mother Suzi and younger brother Colin, 20, develop big plans for

the island moving forward.

Most recently, a volcanic eruption in neighbouring Tonga and increasingly intense cyclones,

as well as rising sea levels means the fate of the island is hanging in the balance.

Josh’s livelihood revolves around the ability of Nukulevu - which lies off the Eastern shores

of Fiji’s biggest island Viti Levu - to host tourists, local guests, and parties. He’s working

around the clock to help ensure his family don’t also lose this idyllic patch of land which

means so much to them.

“It’s been really tough on us you know, as we recently lost our grandpa last year. He loved

the island and spent a lot of time on it with me, I remember these times fondly. So, I want to

do what I can to make sure it’s around for a long time.” Josh says.

Despite being one of the smallest contributors to global carbon emissions, Fiji faces some of

the most devastating consequences of extreme weather patterns of any country in the

world.

According to Fiji’s National Climate Change Policy, since 1993 Fiji has recorded an increase in

sea level of 6 millimetres per year - more than the global average - leading to flooding which

has made areas of the island nation uninhabitable.

Experts believe that if this trend continues the percentage of inundated houses in Fiji will be

around 5% after just 22cm of sea level rise, which is disturbing news considering the

projections for the rise in sea level by 2100 are 1 to 2 metres.

This puts the Fijian government in a tough situation and has forced them to commence large

scale relocations of entire communities, fresh water sources and other major infrastructure.

Josh talks about the measures taking place on Viti Levu currently, saying:

“We’ve actually had some villages that have had to relocate away from the sea, and into the

hills and on the West side of the main island they've demolished a whole mountain ridge to

get small boulders for a sea wall that stretches for about four to five kilometres in length.”

With these large projects taking place on the mainland Josh and his family are concerned

about what will happen to Nukulevu, spurring them to act fast to protect their tiny island

that’s disappearing by the day.

“We’ve built our own sea wall to help combat climate change as well as continuing to add

mangroves to the mangrove forest we have on the north side of the island,” Josh says.

“However, we just recently had a cyclone earlier this month. It was a category one, but our

sea wall still went through a bit of damage. So, it goes to show how vulnerable we are if the

cyclones continue to become more severe.”

Colin was on Nukulevu with some friends during the cyclone, having finished for the week at

university and saw first-hand how the island is at the mercy of the elements.

“You see the shoreline one day and then the day after the cyclone, you can see it's just

moved up closer,” he says.

“It’s just eaten away at the island and you're losing more and more land and you know it's

not going to stop anytime soon. This makes you realise how little time you have and how

vulnerable our little island is, as well as the whole of Fiji and the other Pacific islands.”

The world’s attention was brought to the region when, on January 15, the Hunga

Tonga–Hunga Ha‘apai volcano erupted off the coast of Tonga, 800km away from Fiji,

sending a plume of ash over 30 miles into the sky and triggering several tsunamis, flooding

Tonga’s capital as well as parts of Hawaii and Japan.

“I actually heard a rumbling in the distance which would have been the shockwave from the

explosion of the volcano,” Josh says.

“I'm surprised because we heard the rumbling, but we didn't sort of feel any quake, tidal

activity or any waves, because Tonga got hit pretty badly by the aftereffects of the volcanic

eruption. So yeah, we're really lucky that nothing bad happened on this side.”

Award-winning Science Journalist, Alexandra Witze, says the eruption had been a disaster

for Tonga’s entire population who have had to clear away a thick layer of ash and establish

clean fresh water supplies, estimated to equate to nearly 39 million Tongan pa‘anga or 17

million US Dollars.

“Three people have died in Tonga as a result of the eruption and the overall crisis is being

amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic, which started after relief ships arrived from other

countries, subsequently leading to Tonga facing its first wave of cases.” Witze says.

Having Nukulevu to retreat to meant that Josh and his family were able to get away from

their family home in the bustling capital of Suva, which was where most of the country’s

COVID-19 cases occurred. “Absolute chaos” is how Josh describes the arrival of the

pandemic with people breaking the rules to remain at home.

“The government began closing off certain sections or whole towns and it got to the point

where there was this one guy who got caught swimming across one of the borders in the

middle of the night, probably on his way to get laid,” he says laughing.

Looking ahead, Josh and his brother are continuing to take short-term measures to help

Nukulevu. But their idea of real protection may come from using the island as a way to

educate local people on creating a sustainable future.

Protecting the corals and opening a dive shop would help bring in even more money from

tourism while teaching local people how to use nets that don’t catch undersized fish would

protect fish stocks.

“What we want to do is help educate locals on how to live sustainably so that the future

generations can live off the sea also,” Josh says.

3 - Ukraine crisis exposes bias in Europe’s refugee stance (Double Spread)

Lawran Abdo, 22, fled Syria when he was 11 with his family and they were accepted into the

UK at the start of the Syrian refugee crisis, which remains the single largest displacement

crisis of our lifetime.

“It was a while ago and I was young at the time, but certain things still stick with me,” he

said. “I remember the panic and rush of everything, the fear and desperation I saw in my

parents’ eyes and heard in their voices. I’ll never forget that.”

Around 13.5 million of Syria’s total population of 20 million people find themselves

displaced as a result of the country’s multi-sided civil war, which started in 2011 following

the Spring protests across much of the Arab and North African regions, coupled with the

discontent towards Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

The eyes of the world turned to the refugee crisis in 2015, following the death of Alan Kurdi,

the 2-year-old Syrian boy whose body washed up on a beach in Turkey after he drowned

along with his mother and brother as their inflatable dingey capsized trying to reach Europe.

Yet many Syrian refugees still attempt the same treacherous journey or are in displacement

camps waiting to be accepted into Europe. Now, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine,

Syria’s refugees are witnessing the West seemingly opening its arms to displaced Ukrainians

and, in some cases, changing the same legislation introduced to prevent the arrival of many

Arab refugees.

Claims are growing of anti-Arab bias in European policymaking and in the media.

“It is upsetting if I’m being honest with you,” Lawran said. “Of course, the situation in

Ukraine is very, very serious. But to see England and other countries be so welcoming to

Ukrainian refugees and not to people like me makes me sad.”

Andrew Cawthorne, a foreign correspondent with international news agency Reuters, has

30 years of experience reporting on civil disturbance, war and refugee crises in countries

such as Venezuela and Yemen. He believes these claims of bias are understandable.

“There’s definitely been a sense in the media that these [Ukrainians] are our people, these

are Christian people, who have churches and are close to the West and broadly share our

cultural and religious values,” Cawthorne said.

“There is a coldness or a neglect or complete lack of awareness of suffering people far away,

from other religions, with different skin colours, who to us are so different that we're not

really extending them the same level of empathy and understanding or concrete help.”

The starkest example of inequitable policy changes can be seen in Denmark. The

government’s immigration spokesman, Rasmus Stoklund, recently made comments to the

press regarding the controversial ‘Jewellery Law’ and how it should not be applied to

Ukrainian refugees. The law requires incoming asylum-seekers to surrender assets worth

more than 10,000 Danish Krone (£1200) in order to pay for their stay in the country.

In the UK, public opinion has shown a desire to help Ukrainian refugees in contrast to

people seeking to reach the country from elsewhere. The UK has allowed in 20,000 Syrian

asylum seekers since 2015, whilst since the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on the 24 th

of February, it has accepted 12,000 Ukrainian refugees and counting.

Cawthorne acknowledged that the Ukrainian refugee crisis is “the rallying cry of the world at

the moment” and says it would be reasonable for people in the UK to be more concerned if

“a bomb went off in Wales, rather than if it went off in Ecuador”. However, he sees

underlying racist tones in a lot of the media coverage.

“The sense of a white refugee is one of us, whilst a different coloured refugee is one of them

has been played into for a while now in the UK,” he said.

“The media loves stories of refugees raping and stealing as it plays up to their pro-Brexit,

scary immigrant image they’re trying to cultivate, which has been extremely damaging

considering the data demonstrates how this country has actually benefitted enormously

from an influx of refugees and immigrants.”

Even so, there are limits to the willingness of the British government to help.

A recent whistle-blower report suggested that the government scheme, Homes for Ukraine,

which is meant to help Ukrainian refugees find host families in the UK, was ‘designed to fail’.

Ukrainian national, Natalia Denisuic, has lived in Bristol for the last 5 years. Her sister-in-law

and nephew are about to arrive in the UK after fleeing the Ukrainian capital of Kyiv. The 26-

year-old is more than aware of the preferential treatment her compatriots have received

but explains how she still had to “fight it out to get my family over.”

“Here it hasn’t been easy at all. We signed petitions, attended protests and wrote letters to

MPs. It has been a long process just to even get any scheme in the first place. Then all the

paperwork that was required from us, which is some 80 odd pages. The process became

that much longer.”

Denisuc says she has heard cases of Ukrainians not being allowed in because they lacked the

correct paperwork for their baby “which is the last thing you are thinking about when

fleeing for your lives. People must remember that no refugee wants to leave their home.”

She said she almost failed to get her family to come over from Ukraine in the face of all the

obstacles.

“My family feel it’s so unfair how powerless they are and to be honest it took a lot of

persuasion to get them to leave, they wanted to stay but this is now the last resort.”

When the current Conservative government came to power in 2019, Home Secretary Priti

Patel pledged to keep the number of immigrants as low as possible and critics says she is

doing just that, despite the government’s stated commitment to resettlement.

The government said it would work with global charities and international partners “to

ensure that minority groups facing persecution are able to be referred so their case can be

considered for resettlement in the UK more easily.” (www.gov.uk)

Yet a new policy proposed this year by Patel has been nicknamed by opposition lawmakers

as the ‘Anti-Refugee bill.’ Campaigners say it threatens to break the United Nations 1951

Refugee Convention that protects people seeking asylum. Patel is pushing to have those

who enter the country illegally to be sent to offshore asylum processing facilities in Rwanda,

potentially adding to the number of displaced people around the world.

The policy is part of Patel’s overhaul of the asylum system in the UK. She said sending

people who enter the country illegally to Rwanda would mean “helping to break the people

smugglers’ business model and prevent loss of life.” She added that the law would also

make it easier to “remove those from the UK who have no right to be here.”

Denmark has shown its eagerness to adopt a similar model and there are fears that more

European counterparts will follow suit. Pressure is being put on the Home Secretary to

release framework documents revealing the details behind the resettlement scheme with

Rwanda and show which migrants would be subject to deportation. Her refusal to do so

could possibly see her face High Court challenges.

Claire Garrett is CEO of the Swindon based charitable organisation, The Harbour Project,

which supports asylum seekers and refugees in the area. Over the 22 years since it was

born, after a small group of locals helped a family from Kosovo to settle in the town, the

charity has supported hundreds of displaced people who have been granted access to the

country.

She believes the UK must provide safe and legal routes for displaced people and that it

could have prevented disasters such as the one in the English Channel last year when 27

people drowned after their inflatable dingy capsized on the crossing from France.

Garrett was saddened by the fact that it takes disasters such as that to change public

opinion, saying donations to the Harbour Project went up following the catastrophe, as they

did after the death of Alan Kurdi in 2015.

“We have to accept that people are on the move. Before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, there

were already 82.5 million people on the move at any given time in the world,” Garrett said.

“There is no safe route to legally enter the UK unless you’re one of the lucky few who are on

the planes. We like to say in this country that you are innocent until proven guilty, but if

you’re an asylum seeker the onus is on you to prove you are worthy and have a valid claim.”

Having aided families during the Syrian refugee crisis and now the Ukrainian refugee crisis,

Garrett believes that unless the UK’s “broken asylum system” is mended, Ukrainian refugees

arriving in the future may suffer the same problems as other waves of migrants trying to

reach the country after an initial upwelling of sympathy petered out.

“It’s a very vicious circle. With each wave of people that have come, the government like to

create a different scheme and what that serves to do is to create a hierarchy of worthiness,”

she said.

“Looking back at the Syrian refugee crisis, we were initially welcoming to those who were

airlifted out and brought over by planes, but then turned our nose up at those being

smuggled in and/or coming on inflatable boats. I see this happening with the situation

currently in Ukraine. The stragglers will most likely be treated similarly.”

There are, however, a few countries in Europe that provide some hope to those trying to

flee to safety, which could potentially set an example for the rest of the continent.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, in 2020 the estimated

number of refugees in the European Union was 2.65 million, with Germany accounting for

almost half of that number at 1.21 million. The country also boasts an impressive

employment rate amongst those who have entered the country, with 50% of them in formal

work.

But other European countries have yet to follow in Germany’s footsteps. Campaigners say

that safe routes for entry and a swifter, simpler refugee system is needed, but it’s unlikely

anything will occur if would-be host countries continue to be swayed by public hostility to

refugees.

Lawran and his family were granted access to the UK. However, like so many other refugees

they have found it hard to integrate into the country. Recently Lawran moved to Bristol

after a short stint in Swindon and says that he has only just begun to feel as if he belongs

here, although he still has a dream of one day returning to Syria.

“You know, going to a new school when you’re young is so scary and not being able to speak

good English made fitting in a lot harder,” he said.

“I wouldn’t say I was bullied but I felt like an odd person out,” Lawran continued. “My family

feel this way as well, it took a while for my dad to get a job and mum has struggled to make

friends. I’ve now moved out and got a job, it finally feels like a new beginning and I’m loving

it.”